Oral Presentations

The Basics

Oral presentation, podium talk, pitch—call it what you will, but it is typically some combination of oral and visual communication. The words you say and the visuals you show go hand-in-hand and must compliment one another. But, there is a third player in the mix that entails delivery, confidence, tone, expression, inflection, volume, relatability, humor, and even entertainment. That player is public speaking—an often-dreaded part of life—and with practice, you can be great at it.

Visuals

Your visuals for an oral presentation are usually slides (PPT, keynote, google slides, etc). Making a strong oral presentation rests largely on these slides as your audience will often focus on your visuals as opposed to your face (and sometimes even as opposed to your words). It’s your choice whether you make simple slides with the exact words you intend to speak out loud or compelling slides with visuals that support and solidify your words. (Though we highly recommend the latter).

Quick Tips:

• Good visuals are simple and easy to understand

• They need to be supported by data (don’t make stuff up)

• Make your visuals compelling so that they create intrigue and interest

• Visuals should always be pleasing to the eye, readable and sufficiently resolved

Remember to give your audience space to digest your visuals by incorporating white space and limiting lengthy chunks of text!

Words

Your words and your visuals go hand-in-hand. While the visuals bring your words to life, if you don’t plan your words (i.e. the points you need to make to explain your work), you will find yourself merely describing your visuals, which often don’t convey the full story (or at least tend to give no context or support transitions from one point to the next).

Quick Tips:

Use words to make a connection with your audience

Focus on creating a clear, logical flow from one important point to another

Make it clear you are transitioning sections, concluding your talk etc.

Be concise, but still take care to explain what needs explained.

Public Speaking

When it comes to public speaking, we all want to be calm, captivating, concise, and clear. (Maybe some care to be comical). Unfortunately, most of us were not born with the innate ability to both soothe and entice an audience. If you were, consider helping others.

Quick Tips:

• Accept your imperfection and inadequacy, taking any opportunity to improve your public speaking skills

• Practice, practice, practice, practice (we can tell when you don’t)

• But try to be natural and conversational

Going Deeper

Preparing for an Oral Presentation

There are many opinions and schools of thought around giving presentations. At some point, you’ll be so good and talking in front of people about a particular topic will come so naturally that none of this is relevant. Until then, realize that any preparation is good. BUT your presentation is only as good as the preparation that you do. Here are our suggested steps for that preparation.

1. Identify your presentation aim/objective/purpose – Whether you are giving a talk at a conference, a lab meeting, or in class, asking yourself ‘What do I hope to accomplish through this presentation?’ will give you a good start at laying out your aim/objective/purpose.

Maybe it’s communicating your latest research results, or perhaps you are attempting to inform others about a particular topic. Regardless, if you don’t start by figuring this out, you will find yourself uncertain about the content you should cover.

2. Know your audience – You know your purpose, so next, identify who you are talking to. This should hopefully be easier since you likely know the setting. We encourage you to think past just the age or description of the audience to their particular scientific expertise.

Are they all biologists, and for sure would know the components of the cell? Is it a mixed background audience with some members differing from your field? Are there different levels of expertise? Delving into these questions helps you figure out how deep into the weeds or how broad to keep your talk.

3. Create a story that connects your aim/objective/purpose into the minds of your audience – Everyone wants to follow your talk and take something away. Make it easy for them by creating a concise, logical flow of information. This can be tricky since the process of doing research is neither simple nor linear. Luckily, your explanations to your audience don’t have to follow your exact train of thought. So, step back and get perspective. You maybe took a circuitous route, but give your audience the ‘as the birds fly’ version.

a. Outline breadcrumb points to lead your audience through the story

b. Fill in the knowledge gaps of your audience as your story unfolds

c. Be attentive to transitions

d. Be as concise as possible

4. Produce visuals to support your story – Having good visuals is critical, but they also need to support your story. A bunch of pretty pictures, graphs, diagrams, etc will only get you so far if they don’t match your message. Check out our section on making figures to get a more comprehensive overview. In brief, visuals should be:

a. Make your visuals as simple as possible

b. Ensure data supports your visuals

c. Use them to create intrigue and interest (aka keep people from getting bored)

d. Visually pleasing visuals are critical (choose color pallet, fonts, sizes, etc wisely)

e. Use animations with caution, they can seem gimmicky and childish when used poorly

f. No visuals should ever be blurry, so test on a big screen before your presentation

g. Remember that color sends a message when used in science

h. Word use on slides should be strategic and minimal

i. Make sure your fonts and font sizes are readable

j. Your value in life does not equal the amount of content you can jam on a single slide (sometimes less is more, simpler is better, white space gives people’s minds the space to digest your info)

5. Practice, Practice, Practice – This is the part young researchers seem to despise the most, and unfortunately, it shows. Even if you are a great natural public speaker, an unpracticed presentation is clear to the audience. They may chalk some of it up to nerves and give room for the occasional misspoken word or unclear transition, but at some point, they will lose interest.

a. Practice by writing out what you wish to say

b. Practice by talking out loud to yourself in your room

c. Practice by talking to the empty room in which you will present

d. Practice by actually speaking in front of others and getting feedback

e. Practice portions of your talk by explaining a single visual to someone and seeing if it makes sense

f. Practice however you want, but you still have to do it

g. Refine slides and practice more – Ideally, you get feedback when you practice and can use it to refine your visuals and words and practice some more. You should also use feedback from your audience when you present to at least make yourself notes on what to fix for the next time your present similar info.

Suggested timeline:

start prepping visuals at least a month before presentation

send to your PI (presuming you need to) 3 weeks before presentation

practice with an audience 2 weeks before presentation, then refine slides

practice again with an audience 1 week before presentation, then refine slides

practice on your own throughout this month

Format of an Oral Presentation

Oral presentations usually rely on PowerPoint, Google, or KeyNote slides. The type of oral presentation you are giving may dictate the format, or at least somewhat, or you may have complete freedom.

Typical Sections for a research presentation:

1. Title, authors

2. Background – overarching question or problem and it’s importance (to the world)

3. Approach/methods – how the study was conducted and the rationale behind it

4. Results – use figures to show the important points your work has shown

5. Conclusions – explain your results in the context of the overarching question/problem

6. Future work (optional) – what you plan to do next

7. Acknowledgments (optional) – lab mates, funding agencies, etc

8. Questions slide (optional) – to let people know you are ready for questions

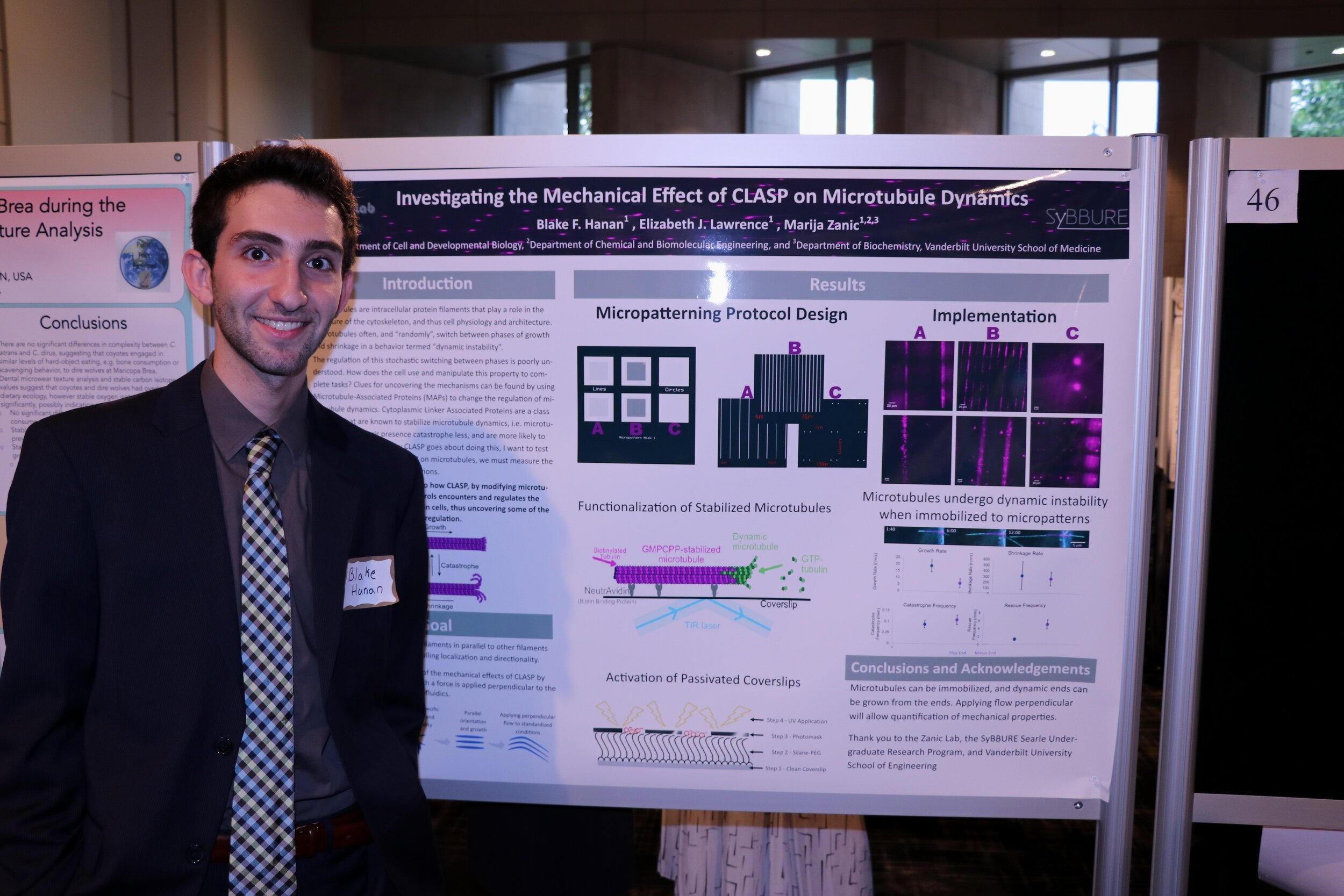

Recommended Format: The Dynamic Visual Abstract

Several years ago, with the aid of our undergraduate researchers, we developed the concept of a dynamic visual abstract. You might be familiar with a visual abstract that many journals require for their articles. It is, in essence, a snapshot of all of the important information about an article. Ideally, looking at that visual abstract gives you all of the important information you would glean had you read the article. You are probably wondering why a long article should be written if you can sum it up in an easier to digest format. But, there is still a ton of important information in the article that isn’t in the visual abstract, particularly for anyone trying to do similar work or trying to validate what was done in the published study.

So, what’s a dynamic visual abstract, you ask? It’s basically that same high-level, easily digestible summary of a study, in presentation form that incorporates all of the typical sections listed above. It is highly visual (more images than text, but be selective with both!) and uses a method of moving through the information in a way that easily leads people from one story point to the next. This style of presentation also should avoid lingo and acronyms (people can’t remember what they are). Either refer to your normally-acronym-ed or lingo-ed term as it’s function or keep the definition on the slide somewhere.

Follow these steps to make your Dynamic Visual Abstract:

1. Start with three panels (background, methods, results), a header and a footer as shown below

2. Create a focused, and if needed, expanded Background panel and fill in the images and brief text that convey the overarching question/problem and its importance

3. Create a focused, and if needed, expanded Methods panel and fill in the images and brief text that convey the what you did to address your question/problem

4. Zoom in on images at any point to make sure your audience can see the details and features that are important!

5. Create a focused, and if needed, expanded Results panel and fill in the images and brief text that convey the data/outcomes you obtained from addressing your question/problem.

6. Create a future work expanded panel to describe what you will do next

7. End with your full dynamic visual abstract to make any final conclusions and take questions

Consider the following advice when you make your Dynamic Visual Abstract:

Critical

The motivation for the project – who it helps and why

Explanations of key concepts other SyBBURE students may not know

Role of the proteins/gene/polymer/etc – use the name only if it is easy to understand

Descriptions of high-level results/take-aways

Results from experiments that provide information regarding your question

A logical report of your progress – doesn’t have to be in chronological order

Summary of what you did, but only pieces key to the picture

Enthusiasm

Non-critical

Your advisor’s personal motivation for the project

Explanations of key concepts other SyBBURE students know

Explanations of non-key concepts

Exact proteins/gene/polymer/etc name or acronym

Results of every experiment performed

Results of experiments performed that do not contribute to answering your question

The convoluted path you took, who you had to wait on, what broke, etc

Summary of what you wanted to do but didn’t get to

Jokes

Giving an Oral Presentation

Calming your nerves – it’s typical to feel anxious or nervous leading up to and/or during your presentation. Try these nerve-calming tips.

1. Practice (obviously this is something you have to do ahead of time, but the more you practice, the less nervous you’ll feel)

2. Stay hydrated

3. Try transforming nervous energy into enthusiasm (do jumping jacks if you need to)

4. Do some deep breathing, through the nose, holding it in for a few seconds, then releasing

5. Think positive thoughts. Even if the worst-case scenario happens, your life will in fact continue! Unless your worst case is aliens blowing up the earth, but that has little to do with your presentation. Think about puppies or kittens or whatever baby animal is your thing, but general happy, positive thoughts.

6. Take a pause, either for emphasis or because you need some calm. No one will know the difference. Take a sip of water if you need to.

7. Validate your nerves. There’s nothing wrong with those feelings, so try not to be hard on yourself about it. Good humans want others to succeed and want to give them space to not be perfect. It’s ok to mess up, it’s ok to give a bad presentation (and learn from it), and it’s ok to be nervous. If nothing else, it shows you care. I promise, it will get better the more you do it.

8. Find a “nodder” in the audience and let their positivity infect you

Propel yourself to success with confidence by:

1. Remembering to introduce yourself and the lab in which you work

2. Making eye contact (or at least look like you are)

3. Speaking loudly (envision talking to those in the back of the room)

4. Using inflection (as long as you don’t have your voice go up at the end of each sentence like you are asking a question when you aren’t)

5. Speaking slower than you think you need to so that you can enunciate each word

6. Pause for emphasis

7. Repeat your important points so the audience has more chances to grab onto them

8. Making it clear you are concluding your presentation and that you are ready to take questions either with a questions slide or by saying something like “and with that, I’ll take any questions.”

9. Talking in front of people often to increase your comfort

10. Forgiving any mistakes that you make

11. Practicing a lot (I know, we’ve mentioned this!)

12. Time yourself so you know you can keep to the time you are allotted

If presenting research results, ensure you are explaining your figures by:

1. Addressing the question that you asked that led to the figure

2. Explaining the axes

3. Explaining the legend

4. Commenting on the methods used to get the data/produce the figure

5. Noting the critical points about the figure

6. Stating the main conclusion and where it led you to go next

Responding to questions

1. No/minimal questions - Conjure all of the grace you can find and say, “I’m happy to follow up at the end of the session or at a later date.” Or include your email and encourage people to send any questions through email.

2. Vague/unclear questions - There is no shame in clarifying, but try not to offend the question asker. Ask, “Do you mean this” or “Is this what you are asking” as ways to encourage them to restate if you didn’t get it.

3. Too many questions - If from one asker, try to politely call on someone else or say “You have a lot of great questions, maybe we should talk outside this session.” If from lots of people, say “I realize I haven’t gotten to everyone, feel free to email me or talk to me after the session.”

4. Difficult questions - Say something like “That’s a great question. I’m not sure I know the answer, but I’ll definitely look into that.” Or, “That’s a really interesting point, I hadn’t considered that, but I should give that some thought.”

5. Really specific questions - Answer, providing you can, but if you suspect they are asking really specific questions because they do similar work, suggest talking after the session or communicating through email.

References & Further Reading

https://undergraduateresearch.virginia.edu/present-and-publish/presentation-tips

https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com.proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/doi/epdf/10.1002/oca.4660110204

https://www.forbes.com/sites/iese/2016/04/18/12-tips-for-public-speaking/#53c760713a18